“I was amazed at how it’s a living ecosystem, growing and accumulating down there. When you’re moving the probe through, you can feel the ground move beneath your feet.”

- Kristina Orpia

Peat depth probe in the ground.

It can be tough work inserting a measurement probe into spongey peatland, but difficulty is a good sign of substance depth.

Kristina Orpia, who helped undertake a comprehensive peat resources survey for Waikato Regional Council this year, says probing some peat sites, such as at Rukuhia, were challenging, but “it’s exciting to lift the probe up and see the material, like all our hard work had paid off”.

Peat depth information had not been collected for the Waikato region since a national survey by the Ministry of Works was conducted in 1976.

The council replicated the survey last summer to get up-to-date information to better understand the vulnerability of our local peatlands to inform any future management decisions that may be needed.

The project sits within a wider peatland strategy to update local peat resource information, prioritise peatlands for investigation and action, test possible mitigations to reduce subsidence and greenhouse gases, investigate alternative land uses for peat, and to develop a good practice guide for future peatland management.

Field assistants surveyed a total of 786 peatland sites.

Kristina, who is studying a Masters of Environmental Natural Resource Management, says getting peat depth measurements essentially required digging a small hole and then jamming a long steel probe through the peat until a solid layer of sand or clay is hit.

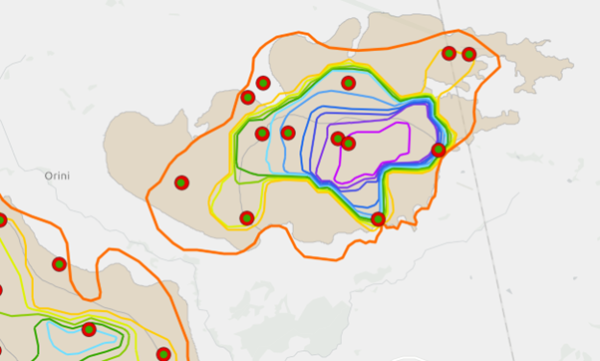

For one measurement in Orini, Waikato district, the team probed their way through 13 metres of peat, unable to push further to retrieve the true depth due to obstruction by sticks. The average peat depth across the region was 3 metres.

So that surface survey methods can be conducted in future, field assistants also captured elevation data used a trimble (surveying equipment).

“I was amazed at how it’s a living ecosystem, growing and accumulating down there. When you’re moving the probe through, you can feel the ground move beneath your feet.”

The Waikato has about 83,000 hectares of organic soils, including the 90km2 Kopuatai Peat Dome. Of this total area, more than 65,000 hectares have been drained, mostly for productive purposes such as pastoral agriculture, cropping, horticulture and peat mining.

Drainage and cultivation have resulted in ongoing peat subsidence, greenhouse gas emissions and, may result in further loss of our peat resource. Unsurprisingly, some of the sites surveyed and mapped as peat in 1976 no longer had peat present, generally at the perimeter of existing bogs in the Hauraki area. On average peat depths decreased by around 1m between 1976 and 2023.

Peatlands upstage tropical forests in their speed and capacity to store carbon. But the key for peatlands to work their magic is for us to keep them wet. When carbon losses are extrapolated across the entire area of drained peatland in the Waikato, they represent over 10 per cent of the region’s gross GHG emissions. Worldwide, drained peatlands contribute to around 5 per cent of the global carbon dioxide emissions resulting from human activity.

Kristina says there needs to be more awareness of the value of peat.

“It’s definitely an important area of environmental management that needs ongoing scientific research.”

Map of organic soils (beige polygon) showing completed sites (red outlined green dot) within the Hoe o Tainui (centre) and Komakorau (bottom left corner) peat bogs at Orini. The coloured lines represent contour-lines of varying depths from the 1976 study results, with oranges/yellows representing shallower sites towards the edge of the bogs, and the blue/purples representing deeper sites towards the centre of the bogs.

To ask for help or report a problem, contact us

Tell us how we can improve the information on this page. (optional)